When Madame Caramel, a 39-year-old professional dominatrix living in London, first picked up my Skype call, she appeared momentarily distracted. "Sorry, when my Skype is on, all my slaves start messaging me," she said. Her hair was wrapped elegantly behind her head, and her smile, broad and warm, radiated as I asked her what female supremacy meant to her.

"Patriarchy has to end. For us to survive, women have to lead," she said. "The way men have done it for over these years... it's not correct. If the women lead the way, there's a much bigger chance there's not going to be any wars, any problems. Men think with their cocks. They're easily manipulated."

Put more simply, female supremacy is the belief that societies should be women-run, and that men, being inferior, should defer to women always. This ideology isn't all that new, though it is extreme: In the 60s and 70s, radical feminist theorists such as Andrea Dworkin, Monique Wittig, and Mary Daly argued for societies in which women ruled, though most of these imagined utopias were separatist in nature. Most infamously, Valerie Solanas argued in The SCUM Manifesto that contemporary society was totally irrelevant to women, and thus "civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking" women had to "overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation and destroy the male sex." (She later told the Village Voice that the group she envisioned in the text—the Society for Cutting Up Men, the eponymous SCUM—was "just a literary device.")

Read more on Broadly

Inside the Strange, Sexual 'Female Supremacy' Movement

These Vintage Business Cards from Chicago Gangs Are Crazy as Hell

Brandon Johnson saw his first gang business card when he was around 12 years old. Nestled inside a cigar box filled with his father's old pocket knives and squirrel pelts was a wrinkled curio ––"compliments," it said, of a group called the Royal Capris. When the preteen inquired as to who Jester, Hooker, Sylvester, Cowboy, and Lil Weasel were, his dad simply replied that a friend had made it in art class back in the day. Later, when he was in college, Johnson dug a little deeper and uncovered a largely untold story about the history of gangs in Chicago.

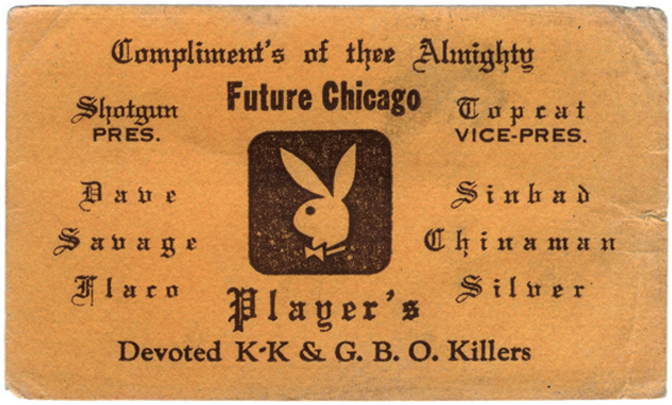

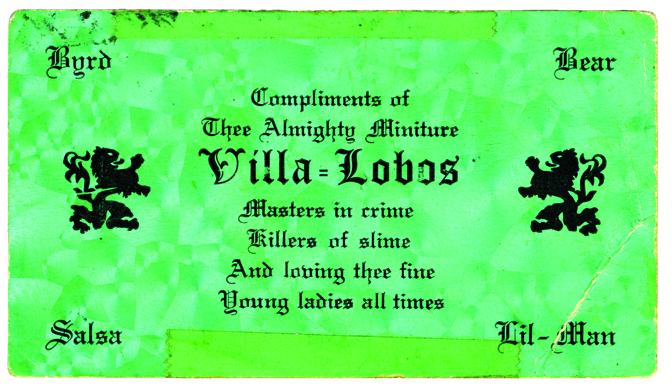

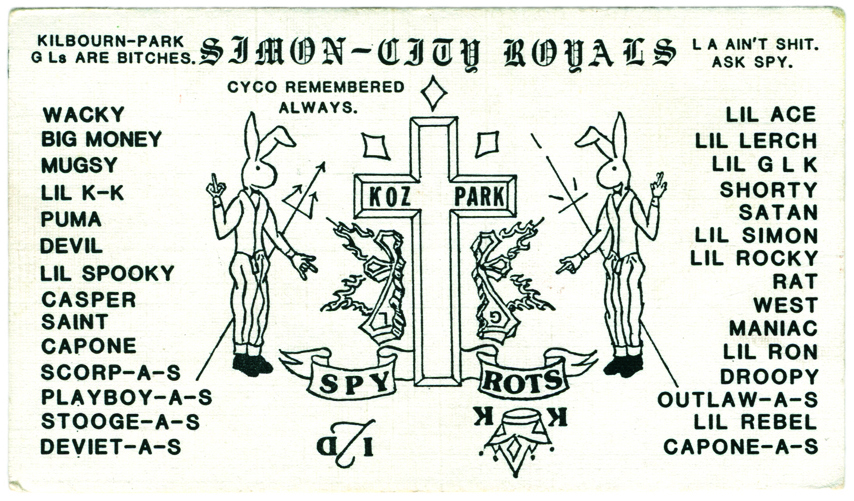

Today, Chicago is one of the most deadly places in America. In 2016, the city saw some 4,300 shootings and over 750 homicides—more than in decades—and some were gang-related. It's tempting to view these business cards as a throwback to a more quaint time given the gun violence currently devastating Chicago, but they actually help tell the story of how it came to be divided along racial lines. Some of the cards are silly and feature graphics like the Playboy bunny, but others feature hooded Klansmen––a reaction to shifting immigration patterns in the 60s and the perception among some whites that their homeland was being threatened.

Granted, Johnson, now 32, has no relationship to any gang violence. He's just a dude from the suburbs with a poetry MFA and a lot of ephemera that's been collated into a book through zingmagazine. I called him up this week to ask how he put together Thee Almighty & Insane, what it can teach us about the history of a deeply troubled city, and why this hyper-specific print subculture went the way of zines.

VICE: For starters, in your research, did you ever figure out who the Royal Capris were and why your dad had their card decades later?

Brandon Johnson:So the Royal Capris were a minor white gang from the Northwest side of Chicago. There's not a lot of history that I've been able to find about them specifically, but my dad grew up kind of near O'Hare Airport in the suburbs and in high school a friend of his was in the Royal Capris. He had actually come to my dad's high school in the last year or two––I think his parents were trying to get him away from the city and gang life so he could finish school. Anyway, my dad befriended him and I guess he just passed my dad that card and he held onto it because it was a cool little token. He put it in a cigar box with some other things from his childhood and it ended up in our attic, where I eventually found it.

Courtesy Brandon Johnson/zingmagazine

How did you get your hands on more of them?

It seems like a lot of it is former members who actually collected the cards while they were in gangs. There was a lot trading when the cards were actually made. So it's just kind of a natural progression from people having collections while in gangs to getting older and getting out of them but still having meet-ups where former rivals would all party together and exchange ephemera like cards and cardigan sweaters with patches. I got my cards through the internet from a former member of the Gaylords who had amassed a very large collection from buying people out over the years. And then also this collector of things of that nature who was a house DJ in the 80s who did a lot of mixtapes, so he knew someone who was selling off a collection of Latino gangs and more rare cards.

What's a typical scenario in which one of these would be handed out? I mean, there's no real contact info or anything on there that could be construed as useful. right?

The contact info was the corner or where they hung out––their territory. I think it was just to rep their gang mostly, for pride of the gang, the prestige of being in a gang. I've heard they were used to recruit, so giving them out to younger guys in the neighborhood and saying, 'Yeah, that's us.' Also I think just as general tokens for affiliation. If they were having a party at a bar or something they could say, 'Show them this card at the door and you'll be good.' And I think they were looking back to social-athletic clubs that existed in the city before their time and what some of the gangs came out of, actually, like softball games and stuff. So membership cards. It was something they adapted from the groups they came out of.

Did the rise of gangs in Chicago have to do with the decline in participation in civic organizations that some historians say characterized mid 20th century America?

I think that might be true of the gangs that came out of softball clubs, but the Latin Kings were a political group in the 60s. And there were greaser gangs made up of high school kids getting together about territory and girls and stuff. What happened in the 70s and 80s was lots of migrations around the city and so things kind of divided along racial lines. The white gangs felt like they were defending their neighborhoods from Latinos who were moving to where they lived, and there was simultaneously white flight occurring. The Latino gangs felt like they were defending against discrimination, looking out for their people, and trying to just now defend a life for their people in Chicago. If you look through the book, you can see for example that the Gaylords have white power symbols and things like that, and I've heard it said that this was more posturing, but it's there. But at the same time, there were alliances that were across races.

Did you learn how to read the cards by diving into urban history or solely by by studying their aesthetic?

I guess a little bit of both. It's evident in the cards who are members of Folk Nation, People Nation––these were started in the late 70s. The Folk Nation was started by Larry Hoover, and he was the leader of the Gangster Disciples and he was in prison at the time and reached across racial lines to create a sort-of alliance. In reaction to this, the gangs that weren't included created another alliance. In the late 70s, this was a big dynamic that occurred. Folk people have different symbols. So you can kind of see who's against each other or with each other. There's a couple books out there written by former members that give first-hand accounts, and other sites that provide history for these things.

Can you talk a little bit about the iconography of the cards? Everything seems to be in almost Olde English, and there's imagery like unicorns, which seems goofy for would-be gangsters. What should the virgin eye be focusing on?

As an outsider, seeing this weird aesthetic, like 'The Almight Midget Gaylords from So-and-So,' you're like 'What does that mean?' But I don't know, it made sense to them in certain ways. Putting symbols upside down means a sign of disrespect, for example. And I think certain things were like stock graphics that maybe the printer had available, because they were using what they had at hand and saw other gangs doing. The design decisions were a bit limited to what they could find or hand-draw.

Check out our VICE News short on how 2016 was the worst year for gun violence in Chicago in decades.

How were these cards made, and did their quality confer special status like in that scene from American Psycho?

There's definitely varying quality, and from what I can tell, they were all made with off-set printers. It seems like there's a lot of local printers throughout the city where the gangs could go to and get 500 cards for 20 bucks or something. Pretty standard business cards, but some of them, like a Latin Kings one I have, is like a glossy gold color with black printing, and that would be a little more premium. Some look a little three-dimensional and have a diamond-effect, which are more desirable as far as collecting them goes.

Can you talk a little bit about how external factors fed a narrative of newcomers versus established groups, and how that helped lead to the formation of these gangs?

In the 60s and 70s, people were abandoning cities for suburbs and there were new migrants coming in around 1965, when Congress made changes in our immigration policies as a result of the Civil Rights Movement. And it allowed people from outside of Europe to come to the US in larger numbers. So there was a large amount of Latino immigration happening, and a lot of them were going to Chicago, because there was a lot of opportunity in the big city. So between these civic projects that were happening like the expansion of the University of Illinois and the University of Chicago, the building of highway interchanges, etc., different groups that had been established like Puerto Ricans who had been there a couple of generations, were being pushed out and evicted. They needed new places to live, so they moved inland a little bit to places like Humboldt Park, Logan Square, Wicker Park. A lot of those people there were moving out to the suburbs because Latinos were coming into their neighborhoods and they didn't like that. So these shifting dynamics and the people who stayed behind felt like their neighborhood was being invaded. This all ended up helping create street-level conflicts between teenaged boys who were almost certainly influenced by older people in their community like their parents who had certain views.

It's unique to Chicago, yes, and that's something I find very interesting and special about them. I'm from a suburb of Chicago, so I have some degree of pride in that city, and I just think it's cool that it's an idiosyncratic phenomenon in that way. I can't say why it only happened in Chicago, but it did, and it's part of it's history and is a unique print subculture that existed right before things went digital.

Learn more about Brandon Johnson's book here.

Follow Allie Conti on Twitter.

It's Been a Long Week So Watch the Bunny Bowl and Kill Time Until the Weekend

Super Bowl Sunday is this weekend, which means that—along with the big Patriots/Falcons game and Lady Gaga and that pseudo-political beer commercial—there are some other sillier bowl games to tune into if you so desire.

The majority of these are animal-based, at least ever since the bizarre Lingerie Bowl has thankfully been put to rest. There's the Puppy Bowl on Animal Planet, the Kitten Bowl on Hallmark, and now, thanks to Annie's (yeah, the mac and cheese people), you can watch some rabbits hop around on a tiny football field during Friday's Bunny Bowl.

The general point of the event, according to Thrillist, is to promote bunny adoption, and all the hoppers you see in the game are available to take home once they're off the field. If you aren't in the market for a new rabbit pet, that's no problem. The last few weeks have been rough and we all need a few minutes to just zonk out and watch a rabbit sniff a football.

Watch the Bunny Bowl live on the Annie's Homegrown Facebook page starting at 1PM EST.

A Family Torn Apart by Trump’s Refugee Ban

The room is dark save for the blue-green wash of light coming off the big-screen TV.

In the other room, morning prayers still play on a radio, muted and distant. Mumtaz, the 3-year-old girl whose explosive energy usually consumes the two-bedroom apartment, is lying on her back watching a cartoon cadre of British elves and fairies imagine a pink unicorn into existence. She mouths the dialogue; she's seen this episode before.

Her mother, Amina Ibrahim, points to the giant bowl of Rice Krispies that Mumtaz has deserted on the kitchen table. "Mumtaz, eat," she says in Somali. The cereal is Mumtaz's breakfast, but also a distraction. Amina is preparing for her regular phone call with Mohamed, her second of four children and Mumtaz's only brother. The family, all refugees of Somalia's ongoing civil war, had to leave him behind with a friend in Uganda when they resettled to Ohio in 2015.

"Why do you hate me, Mommy?" Mohamed asks almost every time they speak. "Why haven't you come for me?"

These phone calls, just a few minutes each, are the only time Amina sees him. Mohamed is now living in Nairobi, Kenya, with a friend of the first friend—a stranger, really, who was kind enough to take him in. He turned 4 in October. The family hoped he would soon join Amina, her husband, and her daughters in the US. They are on top of the paperwork and Mohamed is a just few steps short of the necessary approvals in his nearly two-year-long reunification process.

Read more on VICE News

We Pushed the Lettuce Ban to Its Absolute Limit

Lettuce is a mythical food. According to some sources, you burn more calories chewing it than you gain through its consumption. Whether that's true or not, it jazzes up a sandwich or a burger. So the news of a Europe-wide lettuce shortage is bound to lead to widespread uproar among clean eating freaks everywhere. It has also meant that some supermarkets, such as Morrisons and Tesco, have started rationing the nutritionally-useless plant, alongside other stalwarts such as broccoli. THIS IS A TIME OF WAR, PEOPLE, AND LETTUCE IS FIRST AGAINST THE WALL.

But who is enforcing this ban? If I try to buy four lettuces, instead of the Tesco-ordained three, who the fuck is going to stop me? Can I stock up on lettuces in this, the crisis before the crisis, and sell them on for massive profit over the next few days? If I buy Tesco out of lettuces, what then? And who is going to stop me?

Reader: I decided to go to a bunch of superstores in east London to find out.

This is a photo of some lettuce, and also broccoli. So you know what we're talking about in this article.

First up in our deep-dive investigation was Sainsbury's. They had no formal notice referencing any kind of broccoli or lettuce ban, so I thought I could probably skirt around the rules enforced elsewhere and buy as many greens as my heart desired.

But wait.

No signage, no notice, but no iceberg lettuce. Not a leaf. They probably thought they could get away with acting like nothing was amiss, but I saw those empty boxes. I eyed up that little "iceberg lettuce" ticket. I saw that nothing sat above it, and I wanted answers.

Nada.

So I asked an employee, who told me that there was no lettuce anywhere in the building. None. That there hadn't been any for three days. The store had been desperately on the phone to the supplier to try and get some in, and they were hopeful; but the employee told us with a hint of devastation in her voice that "at this point, the lettuce is looking like a little bit of a myth".

Next, I thought I'd hit up Morrisons, who've proudly spoken to the Daily Mail about their three broccoli and iceberg limit. It seems reasonable enough – stop the people (me) from buying up all the lettuce and selling it onto the black market. What I wanted to see was just how serious they are about implementing this rule.

Again, there was not a whisper of iceberg lettuce anywhere in the building, but they did have broccoli, and they had a little sign warning customers that they would in fact only be allowed to buy three. No going wild and making broccoli soup for the whole family, you; not now, not with a broccoli crisis in full swing.

~FUQ THA RULEZ~

To find out just how harshly Morrisons enforces its new law, I went right ahead and picked up five bits of broccoli. This, I feel, was a reasonable amount of broccoli: not so much that I would deprive all the other shoppers, but enough to test the store's limits.

Walking around with my five broccoli, I started to panic a little bit. I looked around at the other shoppers, politely bowing to the law of Morrisons and buying, at most, two. Heart racing, I walked to the till. Security milled around the doors and I panicked that they might catch me. Would an alarm go off? Would they chase me to the ground and tackle me? What do you have to do to get an ASBO these days?

But no. Barely batting an eyelid, the woman at the checkout let me blithely stroll out of Morrisons, five broccoli in my arms. Take that, limits. Fuck you, rules. Who knew you could get such a thrill in Stoke Newington at 12:30PM on a Friday.

Feeling more than a little amped up after our Morrisons success story, I thought I'd see just how far I could push the reasonable limits of greens-buying in one afternoon. Morrisons might not give a shit about the shortage, but Tesco are a little more upmarket. They've got standards.

And they had lettuce! Finally, for the first time in my actual life, I was happy to see a load of little balls of lettuce. How many? I wondered. How many are in that green basket?

There was no sign near the lettuce, but Tesco had already announced that they would be limiting customer purchases to three, so I figured it was only a matter of time until I got caught. I thought I'd take maybe a few more than in Morrisons. Maybe ten? Ten seems reasonable to push the rules just that little bit. Ten lettuces. Ten lettuces is a feasible amount of lettuce to buy, isn't it? I could be... having a... party. There is nothing suspicious about someone buying ten lettuces at all.

But I just could not stop picking up lettuce. As we're all well aware by now, there's a shortage. I could run out. So I kept going, and going, until my basket was heavy with the burden of 19 lettuces. I got carried away and asked an employee if there were any more, and he said no, but that was OK. I had 19, and the only thing standing between me and a massive, boring salad was the checkout woman.

She was happy to let us walk with our 19 lettuces, until another woman pointed out a sign to her. Purchases are limited to six items per customer. Not of lettuce, not of broccoli, but of anything. Want more than six packets of Maltesers? Nope. There's a great deal on loo roll? Sorry, you can have five, six max. Them's the rules.

I may have walked out with six heads of lettuce, twice the amount in the rule that Tesco had claimed to impose, but I felt deflated. The real scandal here isn't the bad weather in Spain or the fact that you can't have more than three broccoli right now – as if you have ever actually had any need for four heads of broccoli. No, the scandal here is that if you shop at Stoke Newington's Tesco Superstore, you cannot buy more than six of one thing. Where's the justice?

@marianne_eloise / @CharlieBCuff

More stuff from VICE:

How I Almost Died Pretending to Be a Vegetarian in College

I Fertilised My Salad with Period Blood

Just a Quick Chat with the Man Who Legally Changed His Name to 'Free Cannabis'

How Scared Should I Be of My Own Gun?

Welcome to "How Scared Should I Be?" the column that quantifies the scariness of everything under the sun, and teaches you how to allocate that most precious of natural resources: your fear.

When I was a little kid in the crack-addled-gang-members-are-coming-to-kill you late 80s, I wasn't allowed to play with toy guns, the idea being that I might be less apt to become a violent person if I weren't shaped by make-believe shoot-'em-up games. And while the theory broke right apart in practice—my mom says I started chewing all my sandwiches into a gun shape and "shooting" her with them—I did become a peace-loving adult who fears violence in all its forms.

But, for the first time in my life, I kinda want to buy a gun, because I'm surrounded by a media culture that says the apocalypse is coming. Apparently I'm not alone. Several news stories in the past couple of months have told me that liberals and scared minorities are now flocking to gun stores and arming themselves. Don't get me wrong: I don't want to be anything like the people in the dorky group photos of the "Liberal Gun Club," but I also don't want to be missing the single most useful tool in the coming war against—I guess—hordes of Nazi zombies.

But when I recently tried holding a gun that my friend owns—a Sig Sauer P938—I was absolutely scared shitless of it. Don't get me wrong: I liked it. It felt like a well-made metal object, the way sturdy old cameras feel, but I couldn't stop thinking about angling it in the direction that would have directed the bullets farthest away from me if it went off. If I'd had a protractor on me, I would have calculated the exact number of degrees.

As the archetypical deadly weapon, guns are as scary as it gets, assuming you're standing on the business end. But gun ownership is scary too, right? Statistics on accidental death are spotty, but there were 2,191 accidental shootings (including events with no injuries) reported in 2016, according to the Gun Violence Archive, and the kids of American gun owners die at a rate of one every other day.

In total, there were about 58,000 incidents of gun violence in the US last year, according to the Gun Violence Archive, and while we don't know how many incidents affected America's 55 million gun owners, it's likely a large number, since, as common sense tells us, gun owners are more likely to be hurt or killed by their own guns than they are to hurt a bad guy with one, right?

Not so much, Wake Forest University sociologist and gun blogger David Yamane told me. Yamane pointed out that I'm probably citing a paper called "Gun Ownership as a Risk Factor for Homicide in the Home," also known in gun culture circles as the "Kellermann Study," or the "bullshit Kellermann study for asshole libtards."

In 1993, epidemiologist Arthur Kellerman looked at the data and concluded that "keeping a gun in the home was strongly and independently associated with an increased risk of homicide (adjusted odds ratio, 2.7; 95 percent confidence interval, 1.6 to 4.4)." What that influential study actually doesn't say is the thing people often think it does: that you're more likely to have your own gun used against you than to use it against someone else. Instead, "it speaks more to whether [gun owners] should be more afraid of other people's guns," Yamane told me.

Yamane is a gun owner. "Because I have a gun, I feel comforted by that," he said. "I can sleep better at night." But as a sociologist, he knows this isn't the case for everyone. There are gun owners for whom a gun doesn't signal comfort. Instead, he told me, "it signals to them that they always have to be uncomfortable—that they always have to be living in condition yellow all the time—to use the gun code for 'danger.'" In other words, he said, "you're maybe buying the safety, but getting a good dose of anxiety with it."

Perhaps as a consequence, people carrying guns are also 4.46 times more likely to be shot as part of an assault than the gunless. According to Yamane, there's a reason for numbers like these: "If you do something stupid because you have a gun that you wouldn't otherwise have done if you didn't have a gun, then indirectly, your gun becomes a problem for you."

These "indirect" problems for gun owners can be deadly—though they may not involve stupidity per se. Last week in North Carolina, a guy got into a fender-bender, got super angry, and then got out and brandished a gun. It turns out the driver he was mad at was an undercover cop who also had a gun, and the cop killed the angry guy. Back in 2010, a man was acting erratically inside a Costco in Las Vegas, and someone called the cops because he had a holstered gun. After leaving, the cop on the scene shot him to death in what amounted to a very controversial use of deadly force.

It would be facile to dismiss these as cases of people getting what they deserved. After all, having a gun can present a wide range of problems that wouldn't require me to do anything wrong at all. In a 2015 incident that reeks of racism, a black man got tackled by a vigilante in a Walmart for carrying a gun he had a permit for. Last year, a woman in Chicago fired a gun in the air several times to scare off whoever had just murdered her boyfriend, and then got arrested and charged with a crime for pulling the trigger.

These incidents are all examples of what Yamane calls the murky "social reality" of gun ownership in the US. "Despite wanting to draw a bright line between the good guys with guns and the bad guys with guns," he told me, "there are these moments of grayness that come along."

But violence involving other people isn't the only thing that worries me. Guns also make suicide significantly easier, and about 21,000—or 0.4 percent of America's 55 million gun owners—die from an intentional self-inflicted gunshot in any given year. And perhaps only 11 percent of gun crimes are carried out with legally purchased weapons, which means if I own a gun, it could be one of hundreds of thousands per year that are stolen from their owners and used in crimes. I don't especially want that on my conscience.

Also, a horrifying 4.5 million women say an abusive partner has used a gun as a prop to bully them at some point.

But moreover, given my level of anxiety, if I owned a gun, I probably would not take it out and use it very often. Yamane writes about gun owners like me: extreme examples of what he calls "gun culture 2.0." People like me aren't interested in outdoorsmanship or target practice. Instead, we exclusively want to own guns so we can cap Nazis if—or when—society collapses.

In short, it's probably a bad idea to own a deadly weapon if I have no enthusiasm for learning how to use it properly, Yamane told me. "There comes a moment when you have to use it, but it's just been sitting there on the nightstand or in a safe," he said. "I don't know of any cases really in which this has happened, but I think about things that could potentially go wrong."

So anyway, I feel tempted to buy a gun right now, but I have no business doing that, and I don't think you should buy one either.

Final Verdict: How Scared Should I Be of My Own Gun?

3/5: Sweating It

The US Government Says Fewer Than 60,000 Visas Were Revoked Due to Travel Ban, Which Is Still a Lot

The State Department has responded to reports that more than 100,000 people had their visas revoked following Donald Trump's controversial immigration ban, saying that number was actually fewer than 60,000, the Associated Press reports.

Erez Reuveni, a lawyer from the Justice Department's Office of Immigration Litigation, said on Friday that more than 100,000 valid visas had been canceled, during a hearing about a lawsuit filed by two Yemeni brothers who were denied access to the US last Saturday. The State Department rebukes that claim, however, saying that due to expired visas and the types of visas that were exempted from the ban, that number was actually closer to 60,000 or fewer.

Reuveni made the claim at a hearing about Tareq and Ammar Aqel Mohammed Aziz, who had arrived to Dulles Airport on Saturday, had been convinced to give up their visas, and then were put on a plane back to Ethiopia. Airports around the country were plagued by chaos over the weekend, after Trump signed an executive order placing a temporary ban on all refugees and people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US.

"It's quite clear that not all the thought went into it that should have gone into it," Judge Leonie Brinkema, who is presiding over the brothers' suit, said about the immigration ban on Friday.

According to the Post, the government is reviewing a host of similar lawsuits brought on by people who were denied entry to the country, like Tareq and Ammar, and some are being offered new visas if they agree to drop their lawsuits.

It Shouldn't Take a Massacre to Humanize Muslims

Growing up Muslim in Ottawa, so many of my childhood memories are centred around visiting the mosque. The Ottawa Mosque seemed gigantic to me as a child, the brown building complete with a traditional minaret and dome had three main areas: the top floor for women, the main floor for men, and a basement reserved for classes, community events, and extra prayer space on busy nights. On Sundays, my three siblings and I would go to Sunday school not unlike kids of other faiths we knew.

The difference between mosques and other places of worship, from what I gathered, is that mosques aren't really formal settings. We're shoeless, sitting crosslegged on a carpeted floor where it's not uncommon for the person beside you to be taking a nap between prayers. Most mosques I've been to are also littered with children running around and playing while getting scolded by elders to keep it down. Growing up Muslim in a predominantly white city was weird. I always felt like I was explaining myself and my customs, but at the mosque everything kids in my class saw as exotic was normal.

Growing up meant going to the mosque less frequently. Not because I was averse to it in any way, but because going was never an obligation, and I grew out of the Sunday classes. Still, during the month of Ramadan and other religious holidays, the same feeling of safety stayed with me.

Now, mosques are still a safe and familiar space no matter where I am. On a trip to Vietnam last summer, my family and I were wandering around Hanoi when we noticed a hole-in-the-wall mosque where we greeted and talked to Muslims we didn't share a language with—it felt like being home.

Despite all mosques feeling familiar and welcoming, the feelings of safety changed. I felt safe with my Muslim brothers and sisters, but felt an underlying threat as being Muslim became politically charged after 9/11. Islamophobia made us all hyper-aware of how we presented ourselves and existed in our surroundings. As a pre-teen, my eldest sister began wearing a hijab at 22 and told me about how her coworkers began treating her like an alien.

As Islamophobia became a real threat to me as a Canadian, an attack like the one on the Ste. Foy mosque felt almost inevitable. According to a Statistics Canada report from April 2016, hate crimes against Muslims have more than doubled in the last three years. A mosque my brother frequents for Friday prayer, which also doubles as a community hub, has been vandalized multiple times, once even as people prayed.

While Muslims in Canada became almost expectant of attacks, we also became used to silence from our politicians when it came to Islamophobia. Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper has been criticized for staying silent on the growing threat of Islamophobia, while at times also stoking fires to create it. In an excerpt from his book The Relevance of Islamic Identity in Canada, author Haroon Siddiqi went so far to say, "Going well beyond being tough on terrorists, he not only made anti-Muslim talk respectable but also initiated a range of policies and legislation that constituted cultural warfare on Muslims."

Despite evidence that Islamophobia is very much a growing problem in Canada, I haven't heard many frame the issue in a way that feels urgent. Which is why the shock and horror at the Quebec attack only showed me the gulf that exists between me and my fellow Canadians. It takes six deaths and five people in critical condition for most to clue into the uneasiness most Muslims carry around with them. "Even before this, I sometimes imagine someone firing at us praying from behind," a friend told me. Now we all know how possible this is.

Toronto City Councillor Michael Layton embraces Toronto District School Board trustee Ausma Malik after speaking in front of community members gathered for a vigil in support of the victims of the shooting in a Quebec City mosque. Photo by CP/Chris Young

This all plays into the wider context of how Muslims constantly need to be humanized and contextualized by the media when tragedy strikes. A common feelings among Muslims, one that feels almost too cliché to mention, is that we're only represented in media when it's to push a "dangerous" Muslim narrative. In a series of tweets, CTV producer Rosa Hwang chronicled her visit to the Ste. Foy mosque and mentioned, the mosque "is completely non-threatening." While Hwang explained the tweets were not meant to imply mosques are inherently threatening and her guide wanted her to mention the mosque was not scary, I still couldn't help get a bad taste in my mouth. Her guide felt the need to ask her to relay that a small place of worship that was likely also a community hub was not a scary place.

The Syrian refugee crisis has many defending refugees by showing examples of how Muslims bring capitalist value to Canada. In good-natured defenses, we see scores of immigrant success stories. One of the most famous widely shared "valuable refugee" story popularized after the death of child Aylan Kurdi who was found on a beach, is the one of Steve Jobs. Although Jobs wasn't a Syrian migrant or refugee, his birth parents were leaving many to share variations of this tweet, which essentially tells us we wouldn't have iPhones if his family wasn't allowed into America. But it doesn't end with Steve Jobs. Frequently we're reminded of stories about how Ahmed is actually a doctor who saves lives, or a teacher, or some kind of lawyer. Not to mention cutesy stories of how Syrians are, once again, super-harmless neighbours who just want to help us out!

One of the major tenets of Islam is to view other Muslims as your brethren. We all refer to each other as brothers and sisters, even when we don't know each other. A phrase we all grow up hearing is "Love for your brother or sister what you love for yourself," something that goes beyond trying to be literally wishing your luck on others, but to empathize with the pain and suffering of those around you. As I sit here writing this, on the television in front of me I am watching the funeral of three of the men who were killed in Ste. Foy—men and women who look much like my family openly weep at the loss of their brothers. The victims look as familiar to me as the faces I've been used to seeing my entire life. And I can't help but wonder what their inherent value is to non-Muslims if they don't amount to whatever successful immigrant narrative is being pushed at the moment. I wonder whether if we stopped equating the value of Muslims to their potential contributions, something like the Ste. Foy attack could have been avoided in the first place.

Follow Sarah Hagi on Twitter.

'I Am Not Your Negro' Is a Brilliant Documentary About James Baldwin's Never-Finished Book

At the tail end of the 1970s, the decade in which the dreams of revolution that sparked a generation went to die, James Baldwin wrote to his literary agent in order to put forth an idea for a book that he would never complete. The unrealized book, tentatively titled Remember This House, would be an account of the lives and murders of three of his friends—Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X—who are the most revered martyrs of the civil rights causes. Baldwin only finished 30 pages of the proposed booked before dying of AIDS in 1987. Haitian director Raoul Peck, whose previous, wide-ranging work has engaged with the political assassination of a Congolese statesman (2000's Lumumba) and the Rwandan genocide (2005's Sometimes in April), reclaims James Baldwin's quest in his new documentary I Am Not Your Negro.

An Academy Award nominee for Best Documentary, the 95-minute film is narrated by Samuel L. Jackson in Baldwin's words. It delves deep into the author's canon to erect, in bold cinematic terms, an audiovisual analog to the unfinished book. Leaning heavily on Baldwin's late-career film criticism, collected in The Devil Finds Work as much as the Remember This House manuscript, I Am Not Your Negro is a remarkable headlong rush into Baldwin's psyche and the nation's still-unresolved sicknesses of white supremacy and white fragility—the dueling things American liberals used to call, in Baldwin's day, "The Negro Problem." Peck combines archival material from popular films, the author's television appearances, and photographs of Baldwin alongside many of the contemporaries the film eulogizes. These sequences are juxtaposed with footage from more recent scenes of racial unrest, suggesting the continuum between events and eras. The director of as potent an exploration of America's irrational relationship with race as has ever been produced, Peck recently sat down with VICE for a conversation about his new film and the contemporary global political scene.

VICE: When did you first hear of Remember This House?

Raoul Peck: Oh, very late. I already had access to the rights. The estate had given me everything. I could use whatever I wanted. You ask for an option, and it's usually a one-year option that you can renew one, two, or sometimes a maximum of three times. And then they expect you to do the film and to buy the rights. I told them clearly that I didn't know what film it would be. I was experimenting between narrative and the documentary. I spent time with different authors trying to find the right axis, the right story.

Until, four years into it, I just decided the only way to go about it is to be very personal. To do a documentary and to give myself all the freedom I could—politically, artistically, on all levels, in terms of content, in terms of form. And then the question was how do I find the right entry point? How do I tell the film in a very original way, where it would be creative and where I would also feel inspired. That came through the form of these notes. I remember these that were given to me one day by Gloria Karefa-Smart—James Baldwin's younger sister. And that was it for me. That was the idea. The book that didn't exist, and then I said to myself, "Well it did, it's just all over the place of his body of work." So my job was to find it and to reconstruct that work in a very imaginative way, creative way.

And it gave me the excuse, beside those notes, to take out all the stuff about Baldwin that I loved all my life, all the books I had underlined, all the subjects. It gave me not only the freedom, but the access to everything because I could connect them.

Courtesy of Magnolia Pictures

It's interesting that you talk about those connections with his other works, his broader, his milieu. I was immediately thinking of The Devil Finds Work. The historical perspective that he engages film with—it's remarkable.

The Devil Finds Work is basically a deconstruction of how Hollywood—how the media, how literature—basically invented the "nigger," as you would say. It's all there. And this invention is linked with power. It's linked with economy. It's linked with history, and you have all that. So really reconstructing this book is at the same time an attempt to place Baldwin in all these different latitudes and levels and make a story out of it. And a story that would be the essence of all Baldwin.

"History is not the past. This story is the present."—Raoul Peck

One thing I think the film does marvelously is juxtapose footage of contemporary black liberation struggles and the work of past movements, with the sickness of contemporary life as a whole. There's that remarkable montage toward the end of reality television shows, talk shows, and Baldwin's words about how we're creating this false society, which somehow feels prescient in that moment.

The industry deals with this as they would deal with narcotic. But it connects those concerns to the past. It connects that society that we've created to avoid the truth to the tumult of the 1960s and of these three men's lives and Baldwin's relationships with them in that era. And history is not the past. This story is the present. That's an important statement. That means you say you are your history.

Did the new stuff that you shot in New York and in various places grow out of how you were responding to the archival material?

The idea itself was already there, and it was improved as we would go. There was an instance where people were watching and said, "Well, you need to give me a date here, so I understand I can follow." I said, "No. Where I want to go is that we can go back-and-forth without you asking me this question. And as long as you ask me this question, the edit is not where it should be."

We had a very clear idea of what we were looking for. My chief archivist was a French woman, but she knew the US very well. So she would search in the archive here, Library of Congress, and all the companies, but also we would do that in Germany. We would do that in Italy. We found footage about America that only existed on French television. And the idea was also to find images that people don't know that much. The civil rights era—you know those images. I didn't want to use those black-and-white images that we know so much. And people don't watch them anymore. Once you see them you say, "Oh yeah," and then you move on.

"Whatever the repression was 40 years ago, it's the same system, using just better tools."

Seeing, in a couple shots, an image turn from black-and-white to color again suggests this relationship between the past and the present. The continuity of history—your history is here and now. It's today.

That's why I play a lot of those images, because the subject is about creating images and where you don't know what is true and untrue and where color is a sign of modernity and black-and-white is old. And then I turn the images of Ferguson in black-and-white, so that, consciously or unconsciously, you react to that.

Whatever the repression was 40 years ago, it's the same system, using just better tools. But it's exactly the same thing. What it shows you, I hope, is that you need to find the proper response as well. The civil rights movement found a way to organize, and they were solid. Today we have movements, we have anger, we have spontaneous reaction. But are we solid enough to bring a response to what we are going through today? The film questions that, too.

What do you think, personally?

What I think is—it's not so much what I think—it's the facts, the facts of what: They killed most of the [civil rights movement's] leadership, or they bought them. When I say bought—they changed class, they became wealthy. Or their descendants became wealthy, or they became nobility. [Black sellouts] killed a lot of them. Some of them became crazy. Some of them are in exile. So the new generation has basically had no transition, and the few guys doing the transition are the first rappers. And then rap became commercial.

It's synonymous with capitalism.

Exactly. And on TV, the same thing. You could find some sort of, I would say, resistance in Soul Train or the black exploitation film. At the beginning, we thought wow, and then it becomes commerce again.

It's been argued that those films are empty catharsis.

Well, it simplifies stuff and gives you an idea. "Oh well, we are like the other, but we're just black." There is justice in that: This is a black bad guy and a white bad guy. We aren't used to having bad white guys.

Before those films, Baldwin actually talked around these issues in The Devil Finds Work, that black men are desexualized. And in Blaxploitation movies, they are hyper-sexualized.

Exactly.

There aren't black heroes that win, resorting to violence, hyper-violence. Even as belief in the viability of armed confrontation waned among black nationalist groups. And yet in that overreaction, perhaps, those films lost a chance to normalize the struggle for black liberation as well as the sort of lived in real experiences of working-class and middle-class African Americans.

You are right in the de-politicization, because what it said, basically, is [that] it keeps you in the black ghetto. It doesn't give you the big picture. It doesn't tell you that the problem is capitalism. The problem is class. The problem is poor on one side and the rich on one side

Or, as you suggest in the film via Baldwin's text, the NAACP was a classist organization.

Exactly, exactly. This is the dilemma now. By the way, I don't just see Black Lives Matter—I see Occupy Wall Street, I see many other movements that lost their momentum at the very moment when they needed to make the leap into politics. We are a civilization now where there is no more ideology. There is no more scientific truth. There is no more academic truth. Climate change exists, climate change doesn't exist.

You're a filmmaker who's taken on legacy subjects such as Patrice Lumumba's killing or the Rwandan genocide. This new film is very much about the life of a black American and the lived realities of black Americans. What do you think specifically allows you to inhabit, as an artist, these various spheres of pan-African storytelling?

They're not disparate—that's the thing. I was privileged very early on to start to see the connections. And I had decided very early on with the life I was having, the life my parents were having. The only way I can survive is to make sure wherever I am, I'm engaged. I'm in exile. This is something I never accept. I am where I live, you know? My father left Haiti in 1960. And I left in 1961. I was eight, and I went [to the Congo] with the image of Africa that I knew from American films—John Ford and all that. And I could swear to God that when I arrived I would see safari, I would see Africans dancing and smiling, and that's really what I thought. And that was one of the first shocks of my life. I grew up like this.

So it's part of my biography. And I think it's a freedom to never accept whatever other people say I should be. Baldwin said the same. He doesn't wake up and look at himself in the mirror and say, "Oh my God, I'm black, so I'm gonna act as a black man all day." You don't say that. When you grow up in the world, you think about the world. What can I do to change the world? What can I do to change my neighborhood? What can I do?

I have friends who were angry all of their life. I understand this anger. I understand, because it's frustrating. But then how do I tell them, yes, but what do you do? Are you going to do that all your life? Or beat the machine or try something else? Because that's what they want. They want to keep you angry.

Follow Brandon Harris on Twitter.

I Am Not Your Negro is now playing in theaters nationwide.

'WUFF,' Today's Comic by Julian Glander

Behind the Making of 'Dark Night,' the Controversial Film Inspired by the Aurora Shootings

Tim Sutton, whose career began in 2012 with festival-favorite Pavilion, has a brand of filmmaking that's often been compared to the works of Gus Van Sant and Terence Malick—immaculately shot, poetically discursive adventures that find their beauty in existing from moment to moment. He expands on this aesthetic with his third feature Dark Night, which is loosely based on the Aurora shooting from the summer of 2012. Reentering the headspace of James Holmes, who walked into a midnight premiere of Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight Rises and killed a dozen people along with wounding 58 more, Sutton insists that he "didn't want to make a movie about violence," instead claiming that "I wanted to make a movie about the fragility of life."

Inside that visceral depiction of fragility is a movie that polarized audience at its 2015 Sundance premiere. The film, which is seeing release through Cinelicious Pics, won't be playing in a multiplex anytime soon. Understandably, Sutton is frustrated by Hollywood's unwavering aversion to risk: Throughout our conversation, he voiced his discontentment on what he believes is a "marketplace that has turned its back on films like this." He's admirably passionate on this matter. We also discuss his egalitarian approach to presenting a mass murder and how it took him two decades to discover what he wanted to dedicate his life to.

VICE: What's the elevator pitch for Dark Night?

Tim Sutton: We follow six people who end up in the theater—the shooter included. As the sun sets, we realize that the sun will never rise again for these people. We're stuck in the movie theater with them, thinking, What if it were us?

Two investors came in and were going to make it at a decent budget, but they both walked away at different times because they wanted the shooter to be more traditionally evil. I don't think a lot of these people are what we would consider traditionally evil. I think they're disturbed, isolated, hurt, and are seeing the world from a completely different perspective. I'm not saying the shooter is innocent in any way—he does unspeakable acts—but he's a human being, so his screen time is equal to other people's screen time.

So you're OK with humanizing all parties of this equation?

Yeah, because they're all human. What they do is very different, but we're all people, and we're all products of society.

Did you ever consider making the shooter more villainous in an attempt to achieve commercial success?

There's a huge risk in thinking in those terms. It could completely backfire, and then you're glorifying the shooter, who people are equating with James Holmes or other shooters in real life. All of the sudden, you're an even worse guy for making the villain a dramatic, watchable character.

That makes it sound like they're starting with the assumption that you're a bad guy.

Well, I'm not a bad guy, but there are some people out there that are upset that the film exists, and I've been in contact with some people. When you make a film like this, what's important is that people see the film before they make judgment, which is hard in the world of Twitter and Facebook.

When I re-watched the film, it's hypnotic but it's also initially pretty disorienting.

You don't experience life in terms of the more traditional structures of film language—so there's no need to shoot an empty room, have a character walk into the empty room, and have the character leave the room. All you need is one moment that gets enough information across to put you in the present moment.

After the film played at Sundance, what were you feeling?

I thought it was a slam dunk, to be honest. It premiered at Sundance to a lot of hype, and it completely delivered as far as I'm concerned. It created a different kind of audience at Sundance in terms of utter silence and focus, and it delivered a powerful, emotional message. A year later, the film is just getting released. You can imagine how frustrating, disappointing, maddening, and sad that fact is. It should've been bought for a lot of money, and it should've been played in theaters nationwide.

What was the dialogue like with the distributors?

The majority of the distributors love the film, but it's just not something that they're going to take on. Nobody said it's because they're afraid of copycat killings—they just don't think the movie is going to bring them a return on their investments.

How do you feel as an artist moving forward?

I've made three very unique, meaningful art films, and I've made nothing financially. [I made] a little bit of money from Memphis because we got a grant and didn't have to pay it back. I've made films that people say they love, but they haven't made an impact on audiences outside of a very small niche. That's frustrating.

How is it financially sustainable to continue with your career?

I have to get paid to make the next one. I can't just get my producers together, take it all on our shoulders, and shoot a film with half the budget just for the project's sake. I have to raise a proper budget and salary. But Dark Night has helped me get involved in the industry in ways that I hadn't been before—writing adaptations, doing script polishing, and hopefully directing larger-budget films as well.

Listen, I used to live in a big apartment. I don't live in a big apartment. We downsized. It's not the easiest lifestyle, but I finally recognize this: At 25, I thought I was going to be a great filmmaker. But it took me 22 years to figure out what I'm actually good at—what I want to continue dedicating my life to—and that's making meaningful cinema. If I can be a sustainable filmmaker, I'll continue to make films that I feel have meaning. But it's not easy. It's a scramble. It's a hustle.

Dark Night opens at the Alamo Drafthouse in Brooklyn on Friday, February 3; Los Angeles, February 9.

Follow Sam Fragoso on Twitter.

The Battle Over Trump's Executive Orders Is Just Getting Started

Like many new presidents, Donald Trump's first days in office were marked by a flurry of executive actions. Some of these restricted travel and immigration to the US in sweeping ways, some of them were more vague directives for federal departments to do something in the future; a large number of them appear to have been sloppily worded. But by Tuesday, the White House had slowed its roll, delaying a planned action on cybersecurity accountability indefinitely. Rumored executive orders that would restart a CIA "black site" program and legalize some discrimination against LGBTQ people also have yet to surface.

But the decision to on cybersecurity was reportedly less about picking which orders to act on and more about the administration's need to focus on the lawsuits his "travel ban" has stirred up.

That order, which bars refugees and citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the US, is the most infamous and contentious Trump action so far. Early lawsuits resulted in judges declaring that travelers who were en route to America when Trump signed the order should be released from detention. But a number of advocacy groups, including the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), are challenging the entire order, as are the attorneys general of Minnesota and Washington and several large tech companies, who have many foreign-born employees. Even more legal actions are likely to emerge in the coming days, both on this order and others as they move toward implementation.

If you've been having trouble keeping up with all of the cases, you're not alone.

"I have done a chart trying to catalogue [them] as best I can," said Melissa Keaney, a staff attorney at the National Immigration Law Center, which is involved in the legal pushback to the order. "There continues to be minute-to-minute changes to the list. And I think some cases, especially individual habeas actions, are not all accounted for, because they're being filed on such emergency bases that a lot of folks aren't even able to share out the fact that it's happening."

"Altogether, we have a lot of very significant cases pending," Keaney added. "And I think we will be seeing more in the next few days."

Each lawsuit relies on some mix of the following arguments: The order implicitly singles out Muslims for restrictions, violating the First Amendment. It violates the due process guaranteed under American law as per the Fifth and 14th Amendments. It violates the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, which prohibits discrimination based on nationality or place of birth or residence when issuing visas. It violates the 1946 Administrative Powers Act against arbitrary or capricious actions or the abuse of executive discretion, especially when unsupported by substantial evidence of the need for action. Finally, critics argue, it harms the interests of the citizens of specific states.

Many of the anti-ban arguments are very broad, which Keaney told me was necessary due to the order's vague wording and inconsistent implementation—green-card holders were stopped from returning to the country, then they weren't; either 100,000 or 60,000 visas were revoked—making it hard to litigate specific implementations.

Skeptics of the suits have noted that foreign nationals, and especially non-permanent residents, often have fewer rights than citizens, that an older immigration law still allows the president to restrict entry (as opposed to visas) as he sees fit, and that the order does not specifically target religion. (The counter to that last point is that Trump and his advisors have spoken publicly many times about a "Muslim ban.") However, several federal judges have shown sympathy to plaintiffs' arguments when they halted people affected by it from being removed from the US. One Iranian man who was coerced into signing a document revoking his visa was returned to America by court order on Thursday, signaling hope for some with visas who were turned back and are now stranded abroad.

But adding to the confusion, some officials, particularly at Virginia's Washington Dulles Airport, are refusing to comply with court orders. "We have been spending the last few days just gathering evidence of all those various violations in order to obtain additional remedies," Keaney told me. But "it's a very dangerous statement that thus far the administration does not seem to feel compelled to respect [all] of the judiciary's rulings."

So far, these court-ordered reprieves only help those who were already physically on their way to the US soil when the ban was implemented. Citizens of the seven banned countries who have valid visas but are overseas are still barred from entry. And there has been no legal relief for refugees who find themselves suddenly unable to come to America.

The Minnesota-Washington case will have its first hearing on Friday, which could conceivably result in a pause on the entire order in the near future—and, further down the line, possibly lead to a wide nullification of elements of it.

It's relatively rare for courts to overturn provisions of an executive order, says Keaney, especially when national security issues are at play. But Paul Nolette, an expert on attorneys general, notes that courts have been open to lawsuits from states that target the federal government, some of which hampered Barack Obama's immigration-related executive orders.

Trump's other executive actions haven't attracted nearly as many lawsuits, possibly because they have had little immediate impact. San Francisco is suing the federal government over Trump's threat to pull federal funding from "sanctuary cities" that don't comply with immigration authorities, but some critics say that's mere a political stunt.

Keaney told me that many of Trump's actions were unclear enough that most organizations don't know what sort of cases to pursue. "But I certainly think we're going to be seeing a lot of legal action," she added.

Nolette noted that attorneys general have made it clear they're ready to pounce on further actions and will likely have broad strategies ready to go. Key targets for future litigation might center around sanctuary cities, plans for the construction of the border wall, attempts to implement the one-in-two-out regulation restriction, and a bid to guarantee American pipelines are made with American steel. Nolette thinks attorneys general will be especially vigilant on environmental and healthcare issues.

This storm of litigation will continue, in bursts, for some time—and may actually lead to substantial limitations on Trump's boldest designs. The big question, though, is whether this is part of the Trump administration's design or just the byproduct of an inexperienced White House trying to do everything at once. Even before he became president, Trump wasn't afraid of risking suit by, for instance, not paying his contractors what his company had promised. He and his team could be using executive actions and litigation against them like a form of negotiation—ask for everything you want, and see what the courts will give you. Or not. In any case, we shouldn't expect the Trump administration to stop testing just how far the law can bend to its whims.

Follow Mark Hay on Twitter.

Why Was A Six-Year-Old Black Girl Handcuffed By Police At School?

It's been a week since Ontario's education minister Mitzie Hunter ordered a probe into systemic racism at York region school board after a public school board trustee called a parent there a "nigger."

While the horror of that incident is still sinking into the public consciousness, another school board has come under fire for discrimination. This week, the mother of a six-year-old girl in the Peel school district told CityNews her child was handcuffed by police at school. The family is black and their lawyers from the African Canadian Legal Clinic say the incident is an egregious example of anti-black racism.

Police said they were called to Nahani Way Public School in September—the third time school officials had called cops to deal with this particular little girl.

According to Peel Sgt. Josh Colley, "the officers arrived on scene and found a young girl who was acting extremely violent, punching, kicking, biting, spitting. And their first priority is her safety."

Colley, speaking to CityNews, said the officers used de-escalation techniques to try to calm the child down.

"When that didn't work the officers, with the resources that they had, they used what they could to restrain her in a safe manner and ultimately ensure her safety and the safety of the others."

The girl was shackled by her ankles and her wrists.

"It's an insult to think that someone would say that race played a part in the way that we dealt with the situation," said Colley, who is also black.

At times breaking down in tears, the mother, who is battling thyroid cancer, told CityNews "no six-year-old little girl deserves that." She said she's concerned that her daughter feels she did something to warrant being handcuffed.

"I tell her every day it wasn't her fault. She's a good kid… The police have to be held accountable for their behaviour," she said, noting she asked school staff why no one stood up for her daughter and was told, "They're the police, we didn't know what to do. We couldn't intervene."

Reached by VICE on Friday, Peel school board spokeswoman Carla Pereira said school staff aren't calling police per se—they're "asking for first responder support" for a child who may have an escalated heart rate or an anxiety attack.

She said staff would typically try to de-escalate the situations themselves, doing things like taking a kid out of the environment in which they've become agitated, practising deep breathing, have a conversation, giving them calming toys, and calling family members.

"Failing that, if the child still appears to be escalated and we feel there's an ongoing safety risk to the child we would call 911," Pereira said.

She also said unlike school staff, "the average parent or adult might not ever have seen a child escalated to the point where they fear for their own professional safety."

However Danardo Jones, legal director of the African Canadian Legal Clinic, told VICE there is simply no justification for handcuffing a little girl.

"Is there anything else that two 200-pound men could have done to restrain a 48-pound child? Did they try giving her a lollipop or maybe a colouring book with some crayons? The kind of stuff any compassionate adult would do," he said.

Jones said the clinic will be pursuing human rights complaints against the school board and the police.

He took issue with Peel police's description of the child as "violent."

"No one uses that kind of language to describe the behaviour of a baby, of a child."

Jones went through the little girl's history with the school, noting that she had been suspended four times and had the police called her on three times. He said her mother didn't have behavioural issues with her, but for a period of time—while the mother was being treated for cancer last year—she would receive calls almost daily to pick her daughter up from school.

"She was literally having to come out of her sick bed," he said. The girl's father died when she was a baby. Jones also explained that the school called Children's Aid Society but that the organization found there was no parental issue.

Pereira told VICE that schools use a progressive discipline model, looking at things like the child's history, whether or not they're displaying a pattern of behaviour, what disciplinary measures have been used in the past, and mitigating factors such as behavioural disabilities, before taking an "age appropriate" action.

"If the behaviour is repeated, if there's a consistent pattern of abuse… they're going to look at more serious consequences."

She said the superintendent looks into any accusations of racism.

Read more: A New Video Shows a Detroit School Cop Manhandling a Teen Girl

The girl is reportedly now in a different school where she's had no issues. But Jones said she has been traumatized by being handcuffed.

"Whenever she hears a siren she clings to her mother," he said, adding when she sees a cop car on the road, "She tells her mom to slow down the car because she's afraid her mom will get arrested."

He said the incident has sparked numerous complaints from other black parents who say they've had similar negative experiences. And it's shattered a belief that children were somehow safe from racial discrimination.

"This is the purest form of anti black racism. It shows that none of our bodies are exempt for this type of state violence," he said. "I always thought our babies were exempt from this but clearly they are not."

Follow Manisha Krishnan on Twitter.

The Strange Twists of a High-Profile Quebec Hate Speech Arrest

The case of a Montreal-area man charged with inciting hate and uttering threats on social media has taken a weird turn. VICE has uncovered that Antonio Padula's tweets may not only have been misinterpreted by police, but were possibly directed at a xenophobic Twitter account allegedly managed by a Quebec police officer.

On Tuesday night, 45-year-old Padula was arrested by Montreal police (SPVM) and detained for making what were being described as anti-Muslim threats. In the media, police widely used this case to send the message that online hate-mongering — which had reached a fever pitch after Sunday's attack on a Quebec mosque — would not be tolerated.

"Threats are taken very seriously by different police forces and they lead to investigations and potentially to charges," an SPVM spokesperson told VICE.

Padula's lawyer declined to comment on her client's story.

But the irony of the case is that Padula may been using his Twitter account to call out racist views, not to espouse them. What's more, he may have unknowingly attacked an anonymous account managed by an officer with the Sûreté du Québec, the province's provincial police force, who had been tweeting xenophobic material.

Court documents reveal Padula is charged with uttering threats at user @GSloanMDK, or "Arlo The Good Human," whose now-deleted account shared several anti-Muslim tweets and often acted as a troll, as a cached version of their feed reveals.

"Protect the Christians from the Muslims and protect us Conservatives from the Liberals," @GSloanMDK tweeted in January.

The case documents identify @GSloanMDK as Marie-Élaine Gagnon. According to sources with knowledge of the case, Gagnon is an investigator with the Sûreté du Québec.

Neither the SQ nor the SPVM, which is handling the case, would confirm or deny that Gagnon is in fact an employee of the SQ.

Half of the conversation has now been deleted, but here are @Hermit_Spirit's interactions with @GSloanMDK. For context, the two other users Padula called a moron in the threat below had been blaming refugees or Muslims for the Quebec shooting.

While Quebec police received more than 200 reports of online hate-mongering and have made other arrests since last Sunday's attack, it seems the first case they chose to make an example of was a misunderstood case of sarcasm, rhetoric Padula was using to shut down xenophobic trolls.

After the anonymous Twitter handle allegedly being used by Padula was released in court on Thursday, a cursory read of his tweet history revealed a story different to the one being reported by police and media.

In a series of tweets dated January 31, a user with the handle @Hermit_Spirit, who police say is Padula, levelled insults and criticism at a slew of users who espoused anti-Muslim views.

@Hermit_Spirit's brand of writing — short on punctuation, heavy on swears, and often stream-of-consciousness — included such, seemingly sarcastic, asides as "that's exactly what JESUS said — love thy neighbor, except the Muslims...stupid" and "everyone has the right to be a racist prick."

According to court documents, it was the tweets he sent to @GSloanMDK that warranted the criminal charge of uttering threats to cause bodily harm or death. The documents do not indicate which specific tweets or interactions led to the other charge Padula faces, that of inciting hatred.

Follow Brigitte Noël on Twitter

Kenny Omega's Journey from Canadian Junior Hockey Goalie to Wrestling Superstar

If you're looking for the best professional wrestler in the world, you might not find him on national television every Monday night. Rather, you might want to start looking in Japan. If you can't find him there, traipse through eight inches of snow to get to a cottage in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

That's where you'll find 33-year-old Tyson Smith, professionally known as Kenny Omega, one of the best—if not the best—performers working today.

By the end of 2016, it was totally reasonable to argue that he could be considered the best wrestler on the planet. Indeed, there was plenty to back up that hypothesis. On a macro level, he was already a main event performer in New Japan Pro Wrestling, a promotion lauded for being home of the best pure wrestling anywhere in the world. Within the world of Japanese wrestling, he'd already won Match of the Year several times. His performances were so impressive that the company decided to bestow on him an honour that no other non-Japanese wrestler had ever received, as Omega won the G-1 Climax in 2016, NJPW's most prestigious annual tournament.

Then 2017 came along, and Omega's stardom ballooned even bigger after an epic Jan. 4 match with Kazuchika Okada that went down as an instant classic—perhaps the greatest ever—and was celebrated by wrestling fans worldwide.

READ MORE: Okada and Omega's Epic Match Reminds Us That Wrestling's Present and Future Are in Japan

It's been a crazy journey for Omega. There was a time, not long ago, though, when he struggled to even get bookings on independent shows. Flights from his home in Winnipeg were prohibitively expensive for promoters, who could use performers from almost anywhere else in North America for much less. Paying more than they would pay their top talent simply in travel expenses for a WWE developmental dropout just wasn't worth it.

But these days, Omega can't stop his phone from ringing. He doesn't have time to take any of the bookings—not from top American independents, and not even from the WWE, where many thought he would make his debut at the Royal Rumble pay-per-view at the end of January.

For now, it appears he'll stay in Japan as the one of the biggest things in pro wrestling.

Read more at VICE Sports

Inside the Apache Stronghold Fighting Off a Multinational Mining Company

On an all new episode of RISE, our VICELAND series documenting the indigenous communities across the Americas rising up against colonization, we visit the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation where the tribe fights to defend its land against mining company Resolution Copper.

RISE airs Fridays at 9 PM on VICELAND.

Then, catch CUT-OFF, our documentary that takes an immersive look at indigenous youth in communities across Canada as they face states of emergency over suicide epidemics and a lack of access to clean water.

CUT-OFF airs Friday at 10 PM on VICELAND.

Want to know if you get VICELAND? Find out here.

Pentagon Posted a Video from 2007 to Prove the Raid in Yemen Was Successful

The US military released a training video on Friday that it said it had obtained during the recent terror raid in Yemen, only to remove it a few hours later after realizing that the video had already surfaced almost ten years ago, BuzzFeed reports.

The "Lessons in How to Destroy the Cross" video was widely circulated on Friday as a way to demonstrate the valuable evidence the troops obtained during the raid, which was approved by Trump as a way to gather more intel on al Qaeda training and recruitment methods, and resulted in the deaths of one American soldier and ten Yemeni women and children.

While the troops reportedly did find and bring back this video after the raid, it had already been released to the public back in 2007. The military took the link offline a few hours after posting it, and a spokesperson acknowledged that they had not properly vetted the footage before releasing it.

"We didn't want to make it appear that we were trying to pass off old video," Colonel John J. Thomas, a spokesman for the US Central Command in the Middle East, told CNN. "What was captured from the site has already afforded insights into al-Qaeda leadership, AQAP methods of exporting terror, and how they communicate," he said in a statement.

The Pentagon had a briefing scheduled for 2 PM today to provide more details about the military action, because it believed that there was some false reporting on the subject. However, after making this error, the briefing was canceled.

How Trans Improv Performers Are Making Punchlines Less Cis

Improv is an art that requires its performers to think and act quickly; the difficulty of landing jokes on the spot—not to mention collaborating with other performers in a scene as one does so—means that improv comedians have less of a filter than stand-up or sketch comedians. That means a performer's prejudices are more likely to shine through onstage—and sometimes, those prejudices end up reinforcing problematic ideas about race, gender, sexuality, and other marginalized identities in our society.

Chicago's famed improv scene has been accused of perpetuating the entertainment industry's already rampant sexism; other hotbeds of improv talent have been said to lack diversity. Given that our society is already woefully behind in according the transgender community the visibility and acceptance it deserves, how is the improv scene working to make itself positive and supportive for transgender performers? It's a tricky question, given that thought processes behind cisgender privilege are often subtler than those of race and sexuality.

When Colin Jost made a joke on SNL's Weekend Update last November blaming identity politics and the rise of gender diversity for Hillary Clinton's loss in the election, many reacted with outrage. Jost may have argued that the punchline was more a comment on divisiveness within the Democratic Party, but it doesn't excuse the transphobic nature of a joke that makes the lives of transgender Americans out to be politically expendable. If that kind of logic can perpetuate itself on a show that's pre-written and approved ahead of time, it's easy to see how easy it may be for improv performers to make missteps on stage.

Last month, Colin Mochrie of Whose Line Is It Anyway? fame revealed that his daughter is transgender while speaking out about LGBTQ rights on Twitter. It was a positive, uplifting moment—and Stephen Davidson, a London-based trans improviser, wrote an open letter to Mochrie in response pushing him to further encourage the improv scene to stop allowing trans people to be the punchline of jokes. "It's really common in comedy, both improvised and written, for the punchline of a joke to be 'and it turned out the woman had a penis!'" Davidson explained. "That particular punchline is much more troublesome than it seems on the surface, because the implied second half of it is, 'and that's funny because trans people are gross, and I'd never want to be with one.'" It's particularly common among novice improvisers, in Stephen's experience, as "beginners are likely to blurt out any old thing that they think will get them a laugh," he told me.

Both Davidson and Boston-based trans improviser Lorelei Erisis agree that certain improv styles can surface performer biases—such as when one performer plays the "straight man" to another's off-kilter character. "If you have this 'strange' person and the 'straight man,' those two points of view are really based a particular type of normality," explains Davidson. A performer playing a "straight man" is more likely to make anything they feel is out of the ordinary into the "game of the scene"—essentially the joke that makes the scene funny. If their worldview is narrow and heteronormative, jokes are more likely to be based on queerness, gender, and ethnic diversity and other non-normative identities.

Both Davidson and Erisis have worked to create trans-inclusionary spaces within their local improv communities; back in 2007, Erisis founded one of the first and only all-trans improv groups, called the Fully Functional Players, and Stephen runs a group in London called Queer Improv. They're spaces where improvisers don't have to perform under the assumption that the foundational worldview of their fellow players is one of heteronormativity and cisnormativity.