Art by Brian Wallsby

Maureen Tucker had a front row seat to punk rock history being conceived before her very eyes. An average high school girl from Levittown, Long Island, her life was saved by rock ‘n’ roll when she heard the Rolling Stones on the car radio. From the Velvet Underground to Andy Warhol to Nico and Edie Sedgwick, Moe was there—making history herself as the first female drummer in one of the most revolutionary bands of all time.

It was rumored that Maureen joined the Tea Party in the southern state she now calls home, but thank God I interviewed her before the Tea Party was ever even conceived. I hate talking about politics.

ORIGINS

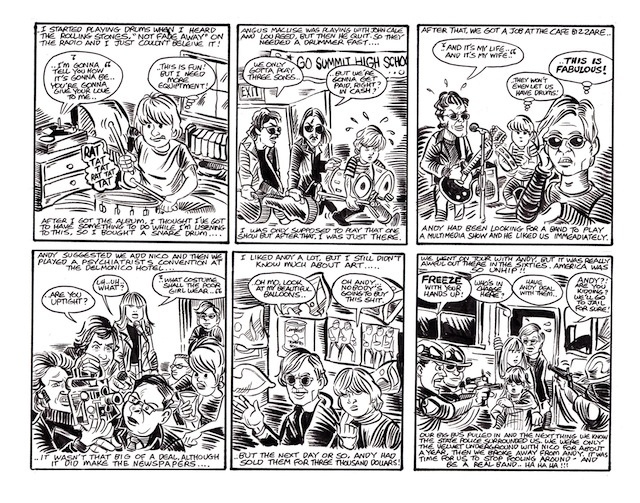

I started playing drums when the Rolling Stones came along, because they were too much for me! I was driving home from work and “Not Fade Away” came on the radio. I almost died. Actually, I had to pull off the road. I was on the Hempstead Turnpike in Levittown and I pulled off the road, I just couldn't believe this. Holy shit, I thought. What's this?

I went directly to Sterling Morrison's wife's house—she was my best friend—and her sister flipped out too. So I zoomed directly to her house and I said, “Kathy! Listen to what I just I heard! Let's go get it!"

We ran to the local department store, bought the album, and went home and played that thing until it was white. We were just like, “Oh my God, this is phenomenal!

Then, a while later, I said, "Well this is no fun. I've got to have something to do while I'm listening to this,” so I bought a snare drum. I was about 19 or 20. About a week after I got the snare drum, Dot Parker's sister bought me a little cymbal with a little stand that you could hook onto the snare drum. So I had this cymbal and this snare drum, and boy, I would sit there for hours, like eight hours, no kidding, and just play that thing over and over. And just play it and play it. That's how I started.

I didn’t know of any other girls that were playing drums, but it never occurred to me to care. It wasn’t an issue. There was never any question by anybody. There was never a remark or a comment by anybody, including other musicians. No one ever said, "Oh a girl playing drums, that’s not cool." It was just no big deal. It seems they make more of it today than they did then.

JOINING THE VELVET UNDERGROUND

I didn’t really audition for the drumming job in the Velvet Underground. I don't know if I'd call it an audition! See, I’d known Sterling Morrison since I was twelve, and Sterling was friends with my brother and my brother had become friends with Lou Reed at Syracuse—they both went to Syracuse University.

That's also how Sterling met Lou. And Sterling had been playing with Lou Reed, John Cale, and Angus MacLise for about six months to a year. Then they got a job where they were going to get paid and Angus thought that was not right, so he quit. So they had this job and they needed a drummer fast. And Sterling knew that I was banging away on drums in my room, so he said, "Oh, Tucker's sister plays drums…."

I’d met Lou once or twice before he came to see me play in my room. He was waiting for my brother or something—he was just hanging out in my living room. But I'd never sat and talked to him. When he came to see me play, I didn't have enough time to decide if I liked him or not—but I came to love Lou.

At Syracuse, Lou and my brother, Jim, were great friends. They spent their college years hanging around a place called the Orange, drinking beers and bullshitting, ya know? That's where they met Delmore Schwartz, as well as a couple of other people, like Garland Jeffries. But I never went up to visit them because I was still in high school, ha, ha!

So Lou came out to hear if I could actually play anything and it was just supposed to be for that one show, at Summit High School in New Jersey. And I was a nervous wreck when we played that show. We were allowed to play three songs and we had practiced them at John Cale's loft. We played, “Waiting For My Man,” “Heroin,” and I think the third one was “Venus In Furs.” We were playing with this band, the Myddle Class, who were a bunch of real handsome boys and the place was packed because they were a local sensation. But the audience was just stunned after we played.

Our set was only about 15 minutes at the most and in each song something of mine broke. All my stuff was falling apart! The foot pedal broke in one song, the leg of the floor tom started going loose. I thought, Oh shit, I'm going to ruin this!

Lou probably didn't even notice. I'm sure he didn't. I'm sure he was nervous enough as it was—not that he was nervous about playing, but this was like playing a supper club, the audience was sitting in upholstered seats. And I had these horrible drums—I only had a snare drum when I first started trying to play. And then my mother saw an ad in the local newspaper for a drum set for 50 dollars, so she bought it for me. It was fine. I was just fooling around, but you can imagine this total wreck of a drum set.

But I just kept playing, hahaha!

ANDY WARHOL

We played that show and then immediately got a job at the Café Bizarre, where you weren't allowed to have drums because it was too noisy. So Lou said, "Well, just come and play the tambourine…"

So I went and played the tambourine to “Heroin,” and it was kind of tricky, haha! From then on, I was just there. But there was never any official, "Okay, you're in the band…"

I believe it was Barbara Rubin that brought Andy Warhol to see us play at the Café Bizarre. It was about the third or fourth night we were playing there and I was impressed by Andy. I knew who he was; of course, I knew he was hot shit at the time. Andy was always in Time magazine. And I thought, Oh, that's cool, ya know?

I'm not much into art. I'm very bad at art as a matter of fact, I don’t know nothing about it. I know what I like—and I did think the tomato soup cans were kind of cool, but that's really all I knew about Andy. Apparently he had been looking for a band to play with this idea of having a multimedia show. I guess you can call it a show. And Barbara Rubin thought we would fit the bill.

Andy liked us immediately and we just talked about his idea for the multi-media show, which, at that time, was still just an idea. Then he asked us if we wanted to do this, and we agreed.

The Café Bizarre fired us shortly after Andy came to see us. The manager or the owner said, "If you play another song like the “Black Angel’s Death Song,” you're fired!" So we launched into another song like that and we were fired. Which was fine with me, because it was Christmas week, and I didn't feel like spending Christmas Eve at the Café Bizarre. I was glad we got fired.

I lived on Long Island; and I would come in to the city every weekend to hang out at the Factory. It was just great. It was like a bar, ya know? A good place to hang out with all sorts of interesting people, like Ondine, Gerard Malanga, Ronnie Cutrone, and all those other people, and they were funny as shit. I’d just lie around and watch Andy make drawings, ya know? Andy was great. I really, really liked him a lot. We had a lot of fun. So we really had a good time at the Factory.

I was totally naïve. I had never been anywhere or done anything and here I was sitting in the Factory with Andy Warhol. I was very insecure and shy—that’s why I wore shades on stage, I was embarrassed! And Andy could have very easily made me feel like shit, just by not talking to me. That would have done it, ya know?

But he was never like that. Andy made me feel not just welcome—but very welcome, and that meant a lot to me. I liked him a lot. I used to call him, “Sweets.” Andy was famous for being cheap and I would drive in for the weekend from Long Island and I needed money for gas to get home. In those days it took two dollars to fill the tank and I'd say to Andy on Sunday afternoon, "All right Sweets, I need some money…”

Andy would be like, "Oh, oh, just a minute…"

And he would wander off somewhere, hoping I'd go away! It turned into this shtick and everybody would be waiting for me to start the fight with Andy and chase him around the Factory. You know, "You son of a bitch, give me some damn money!"

"Oh, oh, oh just a minute Mo…"

Andy had these silver balloons he was making. I guess it was art, something I didn’t know shit about. So when he first was doing the silver balloons, I came to the Factory on the weekend and he was just finishing them. There was maybe four or five of them floating around, I walked in and Andy says, "Oh Mo, look at my beautiful balloons…”

I said, "Who do you think's going to buy this shit?"

Andy said, "Oh, oh, oh, oh no, people will like them…"

Then the next day, or a week later, he sold them for $3,000!

Boy Andy worked like a dog. He was always working, if not actually creating art—he was on the phone, planning something. He’d say to Lou and John, “You have to write a song every day." I don’t think he said it every day, but I remember it as a joke, but not really a joke. Ya know, "How many songs did you write today Lou?"

They’d say, "Two."

And Andy would say, "Only two?"

Andy Warhol, Maureen Tucker, and Lou Reed

NICO

Nico came in pretty early, the reason I'm saying that is because we have pictures of her singing with us in the Factory when we were just fooling around. And that was real early, at the old Factory. Andy didn't bring Nico up to me in particular. He didn’t push her on us, because we wouldn’t let anyone push us into anything. I'm sure he just said "Hey, maybe she should sing a song…"

And we said, "Well, we'll try it..."

I think the songs Nico did sing were great, and none of us could have come anywhere near singing them the way she did. But Nico and I didn't really have anything in common. I didn't dislike her, but we never really sat around talking. She was from a whole different world than I was. I mean, I was this goofball from Levittown ya know? I mean how cool can you be if you’re from Levittown? And she was this Nordic beauty!

About ten years ago, well, it was probably twelve to fourteen years ago, I was living in Arizona and playing with some kids, we had a little band and we got a job to play a gig in California. And when we got there, we saw Nico's name on the Whiskey a Go Go marquee, and I said, "Oh, should I go?"

I hadn't seen her in almost 20 years and, as I said, we were never great friends, we weren't enemies, but we weren't friends. I really didn't know if I'd just get a bored, "Hey, how're you doing?”

But I said, "Maybe I should go say hello to her…?"

So I went back to the Whiskey when I knew she'd be coming in to do her show and she was just thrilled to death to see me. It was so nice. I'm so glad that happened, especially since she died. She really was happy to see me. So after her show—and mine—we met back at the mote. Nico, me and a couple of her people and a couple of my guys sat around drinking beers and talking—and it was really nice.

Right when Nico came into the Velvets is when we played the Psychiatrists Convention at the Delmonico Hotel. Holy shit, that was so funny. Why they asked us, I don't know. It wasn't like a concert; it was like dinner with two hundred psychiatrists and us—these freaks from the Factory. We played maybe two songs or something, and afterwards people like Gerard Malanga and Barbara Rubin assaulted the audience with their tape recorders and cameras, going to tables and asking these ridiculous questions. And the psychiatrists were flabbergasted. I just sat back and said, "What the hell are we doing here?"

I guess all these shrinks thought maybe they'd take notes or something, ha, ha, ha!

It didn’t get much publicity, there was one little story, it was just something like, “WARHOL'S NUTS GO TO PSYCHIATRISTS CONVENTION!” And it got mentioned in the New York Times, but it wasn't a big affair. I mean they were just having a convention and I guess they needed some entertainment, so they got all the freaks from the Factory, ha, ha, ha!

THE DOM

We used to play at the Dom on St. Marks Place and we had a great time there because it was just us, We rented the space and we would play three or four times a night for a half hour and in between sets we would play records—whatever we wanted. Of course, we brought our own record collections. Lou had a great singles collection, things you never heard of, but each one had this wonderful guitar solo or great bridge or some other great hook. I remember playing River Deep Mountain High so loud that I can't even describe it. It was incredible cause it was big, and, oh man, we played whatever we wanted. So all night we'd hear the music we loved and when we weren't doing that, we'd make music.

We played at the Dom for like a month, and all our friends from Long Island would come in on the weekend and we'd have our own Levittown party, ha, ha! We played every night and there were always people at the Dom. It was always full. And then on the weekends, of course, it was packed. And Andy would be in the balcony with his lights and stuff and we'd run up there in between sets and give him some shit, ha, ha!

It was fun, we had a good time.

But then my drums got stolen, my 50 dollar drum set that my mother bought me. We go there to play and my drums were gone—someone had stolen them. So me and our helper, who had a station wagon, drove around looking to steal some metal garbage pails to use as drums. We found a pair, but they were kind of yucky, so I said, "No, let's keep looking..." So we found the cleanest pair we could and stole them and that's what I used for three or four nights, maybe a week. But that’s the only thing I've ever stolen in my life, as a matter of fact.

The garbage cans sounded great, though. They really did. And I used mallets and we had little contact mikes that we under each drum. The first night the drum was under this pile of yuck that had come off the sides of the can, so we cleaned it up, of course. And the next night the pile of yuck was smaller, and the next night, it was even smaller. Each night I was beating more shit off the inside of the garbage can, so the pile was getting smaller and smaller every night.

Then Andy used our earnings from the Dom to buy me another used set of drums. I always got the shit. The drummer always gets the shit, ha, ha, ha! But we had a real good time at the Dom—it was just like sitting in your living room.

After we played the Dom, we went out on tour. I think we even went to California and stayed at the “Castle.” That was a lot of fun, but not California. We didn't like that peace and love shit, ha, ha, ha! We didn’t like hippies. And we weren’t big fans of the San Francisco sound. We weren't into that stuff, ya know?

Not at all.

When we played the Trip in LA, the sheriff locked our stuff in the club. I don't really know what happened, it wasn't something we had done, it was something the club had done. I just know that when we went to pick up our stuff and it was locked up and we couldn't get it. That got resolved after a few days, but in the meantime, we were in the “Castle” for a couple of weeks, waiting to go play the Fillmore in San Francisco.

And none of us got along with Bill Graham, the owner and promoter of the Fillmore Auditorium, he was a real shit to us. First of all, he threw Sterling out, and when we went on, he said something like, "I hope you fuckers bomb!"

He hated us cause we were from the East Coast. We didn't do anything to him to make him hate us. He just didn't like us from the start and we didn't like him either, so fine.

Unfortunately he is known as the inventor of the light shows and shit, sorry, but we were doing that first. I don't really give a shit except that his reputation is that he started the light show, when he had like two spotlights and maybe a strobe light.

But he didn't start all that, Andy did.

When we were on the road, everyone completely respected me going to Catholic Church on Sundays. I mean they'd tease me and go off on a trip, but every Sunday morning, I’d say, "I need a car to go to church..."

So they'd tease me a little bit, but they respected that a lot and I never had any problem because of it. And when Andy was going to start making a movie now, they’d say, "Oh Mo, we're going to make a movie now..."

And I'd say, "Well, see you," cause I didn't want to see that shit, ha, ha, ha!

The first record we did with our own money. And then we shopped it around. We just recorded it—and then the idea was hopefully a record company would buy it. We didn’t we didn't have a hell of a lot of time; the first record took eight hours. And then, when Verve bought it, they gave us a little more studio time, like five hours or something in California.

Our record company, Verve, never paid royalties and they never distributed us. We’d go play somewhere, in Philadelphia or Boston, and people would pack the place and love it and then say, "Oh we can't find your record!" Everywhere we went, same old thing. I don't know why they signed us? To keep us off the streets? It was a mystery. I mean, why did they sign us? For tax reasons? So they could write us?

So we got screwed by Verve.

THE ROAD

It was also scary touring middle America in those days. John Cale’s hair was about shoulder-length and people would actually say things to him on the street— a guy punched him in Chicago, of all places. Just for having long hair. People were so unhip.

Our bus got stuck in Ohio once and luckily there was a gas station right there. So our big bus pulled in and out pops these thirteen lunatics, and the attendant called the police immediately. So we get out and we sent the most normal person, Sterling Morrison, out to talk to the guy, "Hey do you have a distributor?"

Everybody was out of the bus to stretch our legs and the next thing we know there's State Police surrounding us, saying, "Who's in charge here?"

Someone said, "Andy..."

Someone else said, "No, don't send Andy out!"

We told the cops, "Hey it's broken, we're stuck! What are we going to do?"

It wasn't dark yet, but it was obvious we weren't going to fix it by nightfall. The guy had to send to Detroit to get a part for us, so it was going to be overnight. And the cops told us, "Well you be out of here by noon tomorrow!"

And we had done absolutely nothing wrong. So we go to a motel and we got two rooms. The girls were in one room and the boys were in the other. So we're sitting there, in the middle of nowhere, and there was a honky-tonk bar down the street, so Sterling and I went to get a beer. When we got back, we all went in one room to drink beer and watch TV—and the manager called to complain—cause they were very pissed off that the girls were in the boys' room.

It was nuts.

When we got back from California, Albert Grossman, Bob Dylan’s manager, had stolen the lease to the Dom and renamed it the Electric Circus. It was supposed to be ours and while we were gone, Grossman had somehow wrangled the lease from the landlord. He said, "Oh they left town," or something. So when we came back, he was running it, so we didn't like Albert Grossman too much either, ha, ha!

We were the Velvet Underground with Nico for about a year, when we were doing the Andy thing. I would say it was about a year, maybe a year and a half. I don't think there was a point when someone said, "Nico’s out of the band..."

We just kind of drifted.

This is a pure speculation on my part, but I don’t think Nico thought of herself as a singer at that point. I think she saw herself as a movie person and a model—and singing with us was just something to do. And maybe having sung with us, she thought, Hey this is neat, I'm pretty good at this! And then she pursued it further, but that's just my opinion.

About that same time, we broke away from Andy. It was just time for us to leave, and stop fooling around—and be a real band, ha, ha, ha!

I don't really know what happened between Lou Reed and John Cale either. I think they just clashed—not all the time—but towards the end there it was just too much of a fight going on. It was about music, but I don't know specifically if John wanted to try this and Lou didn't, or what. But I was hurt by John leaving the band. It was very painful for me. I really like John, not just musically—so it was just a shitty situation.

John still wanted to continue having a band; I guess he thought; Now I’ll do my own stuff… So it wasn't a matter of, “Should we be in John's band? Or Lou's band?” It wasn't like that. It was just like, “Well alright, we'll continue as a band…”

But life's such a drag when that happens.

All throughout my playing with the Velvets, I never thought of it as a career. I never thought of being a musician as a career. It was just that we were having fun and making good music. After the band was over, it was time to get a job.

So Andy hired me to do some transcribing. I'd go to the Factory at Union Square and listen to the tapes and type them up. Andy was making movies and all this shit's going on—and I was sitting there typing away. After about three days, Paul Morrissey came over to see how I was doing and he noticed all these blank spots on the pages. I was leaving blanks.

So Paul said, "What's this?"

I said, "Oh I'm not putting in these disgusting words."

I mean Bridget Polk was cursing and other people were talking dirty on the tapes, and it bothered me, ya know? So I was leaving blanks, where the dirty words went. I was leaving the proper number of spaces for the letters so they could fill it in later.

But Paul went and told Andy, and he comes running up and says, "Oh, oh, oh, Mo you're not putting in the curse words?"

I said, "No, no, you know I don't like that kind of talk."

So he said, "Oh, oh, well could put in the first letter?"

I said, "No, no you'll have to go back and figure it in."

Andy said, "Oh, okay,"

So they had to go back and fill in all the dirty words.

%20vdc.jpg)